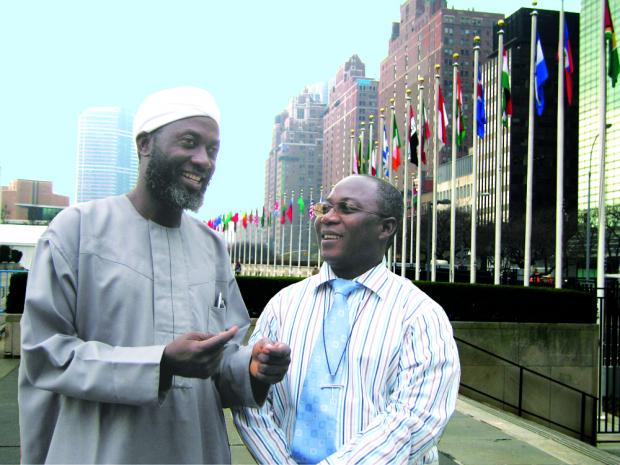

A Muslim imam and a Christian pastor: former enemies, now internationally renowned peacemakers. Two Nigerians have been taking their message of hope around the world. Mike Lowe reports.

In a suburb of Melbourne a young man waits patiently in line to speak to Imam Ashafa. The crowd in this modern auditorium has mostly dispersed, yet around each of the main speakers – an imam and a pastor from Nigeria – many are gathered, trying to catch a word. Finally, after nearly half an hour, the young man gets his chance to tell the imam that he had hated ‘your people’ – the Muslims – so much. ‘I’ve done things [to your people.] You changed my world today. Please forgive me.’

In a suburb of Melbourne a young man waits patiently in line to speak to Imam Ashafa. The crowd in this modern auditorium has mostly dispersed, yet around each of the main speakers – an imam and a pastor from Nigeria – many are gathered, trying to catch a word. Finally, after nearly half an hour, the young man gets his chance to tell the imam that he had hated ‘your people’ – the Muslims – so much. ‘I’ve done things [to your people.] You changed my world today. Please forgive me.’

Nigeria is Africa’s largest country, with a population of 140 million. It is one of a number of African countries where Christian and Muslim populations live side by side. Imam Muhammad Ashafa and Pastor James Wuye began their present work 14 years ago, after leading rival militias in clashes between Christians and Muslims that killed many thousands. In the fighting, the imam’s spiritual teacher and two cousins were killed. The pastor lost his right hand. Now they say that the true Muslim forgives and that the Christian cannot preach hatred.

Their work came to the attention of IofC’s FLTfilms in London. The resulting documentary, The Imam and the Pastor, tells the story of their remarkable change, from sworn enemies to creating and heading the Muslim-Christian Interfaith Mediation Centre, based in their home city of Kaduna, northern Nigeria, which has been credited with saving many lives. Their model for religious harmony has been adopted by the Nigerian Government.

The Imam and the Pastor was launched in December 2006 at UN headquarters in New York, in the British Houses of Parliament and at the International Conference Centre in Nigeria itself. The film won first prize (short documentary section) at the Africa World Documentary Film Festival in St Louis, Missouri.

2008 has been a remarkable year for the imam and the pastor, taking their film and its message around the globe. In addition to their ongoing mediation work in Nigeria, they have been invited twice to Kenya’s Rift Valley Province to help with trust-building work between tribes involved in post-election violence earlier in the year. Thanks to a grant from the US Institute of Peace, this work has been filmed with a view to producing a follow-up documentary looking more specifically at their peace-building methodology.

In January the two men travelled to western Canada to engage with ethnically diverse communities in seven cities. Their example inspired Imam Syed Soharwardy from Calgary to set out on a six-month ‘walk for peace’ across Canada enlisting Muslims and Christians to wage a ‘jihad’ (struggle) against violence. Soharwardy told reporters that he took inspiration from The Imam and the Pastor because it portrayed ‘two faith leaders who would continue to maintain that their own faith was the one they would proclaim, while committing themselves to eschew violence against the other’s leadership and beliefs’.

In January the two men travelled to western Canada to engage with ethnically diverse communities in seven cities. Their example inspired Imam Syed Soharwardy from Calgary to set out on a six-month ‘walk for peace’ across Canada enlisting Muslims and Christians to wage a ‘jihad’ (struggle) against violence. Soharwardy told reporters that he took inspiration from The Imam and the Pastor because it portrayed ‘two faith leaders who would continue to maintain that their own faith was the one they would proclaim, while committing themselves to eschew violence against the other’s leadership and beliefs’.

A few weeks later the two men returned briefly, at the request of the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) for a screening of the film to DFAIT and other government department officials and representatives of NGOs. Introducing the men, David Angell, Director General of the Africa Bureau and former High Commissioner to Nigeria, said that of those working to effect change, the imam and the pastor ‘are not only among the most inspiring but among the most effective’.

April and May saw the premieres of the French and German language versions of the film in Geneva and Berlin respectively, followed by a French premiere at the International Salon for Peace Initiatives in Vilette, Paris. The two largest circulation newspapers in French-speaking Switzerland each carried major articles on ‘The imam and the pastor: two war-leaders converted to forgiveness’. The film was later shown on Swiss television, in German and Italian. It has also been shown on Swedish TV.

October saw the men return to Geneva, and then to Paris, for screenings of the film at Cinéma Verité, the world’s most prestigious celebration of films that highlight humanitarian and social causes. Other guests included Queen Noor of Jordan. Nobel Laureate Wangari Maathai, IofC International President Mohamed Sahnoun, Bob Geldof and Meg Ryan.

A few weeks later the Nigerians headed to Australia for a three-week tour of four state capitals and the federal capital, hosted by Initiatives of Change. Interviewing them on ABC’s popular Late Night Live programme, veteran broadcaster Phillip Adams was moved to declare, ‘I am talking to two people who are, quite clearly, amongst the most important people in the world at this moment of our troubled history.’

In Melbourne, their visit had the backing of the Islamic Council of Victoria, the Victorian Council of Churches and the Victorian Multicultural Commission, helping their message reach Christians and Muslims alike.

In Brisbane, some came armed with scripture to find fault with Christians and Muslims working together. ‘We don’t have full agreement on beliefs and values,’ they responded, ‘but we are children of Abraham and sons of Adam and as such have a duty to each other as fellow humans.... It is not about compromise. It is about creating a space for the other.’

Imam Ashafa explains: ‘The Koran teaches that Islam is inclusive and acknowledges other religions. All those who believe in God have their reward. Mischievous religious leaders with the help of political interference have led people to follow hate and twisted the teachings.’

Pastor Wuye responds, ‘The Bible says to pursue peace with all men, and holiness, without which we cannot see God. When Ashafa sought to show respect and compassion and seek forgiveness I was troubled and wept: “How can I forgive this enemy of mine who has killed my countrymen and caused the loss of my right hand in the fighting?” Just as his prophet had led him to forgiveness, so did Jesus challenge me.’

Ashafa acknowledges that it has been hard. ‘We are held in suspicion in some parts of our communities. The biggest enemy we have to overcome is ignorance.’

In Canberra, the two Nigerians were special guest speakers at a seminar for 200 following the 22nd annual National Prayer Breakfast in Parliament House. Never before had a Muslim taken such a prominent part in this event. When asked what each had had to compromise in order to work with the other, both replied with an emphatic ‘nothing at all’, which drew spontaneous applause.

From Australia they travelled to Cyprus where they were panellists at the annual ‘World Prayer for Peace’ sponsored by the Catholic St Egidio Community and the Orthodox Church of Cyprus. In this small country, tragically divided between Greek/Christian and Turkish/Muslim communities, their experience was especially relevant.

Communal relations in some parts of Nigeria remain tense. The Interfaith Mediation Centre is on constant stand by to send task-forces of imams and pastors, trained by Ashafa and Wuye, to deal with ethno-religious conflict anywhere in the country.

The incontestable message of the imam and the pastor is that peaceful coexistence between Christians and Muslims is possible in Nigeria and throughout the world.